Sarah Van Beurden is an Associate Professor of History at the Ohio State University and a visiting scholar in the Department of African Studies at Ghent University. She is the author of Authentically African: Arts and the Transnational Politics of Congolese Culture (2015.)

As a researcher on museums in DR Congo, I am often asked whether museums are even relevant to a place that has many pressing problems. It is a legitimate question, and yet, I am continuously surprised at the museum projects I keep encountering there. Some are never completed, others temporary, and there are also those – like this small family museum – that demonstrate a robust confidence in the ‘modernist dream’ that is the museum.

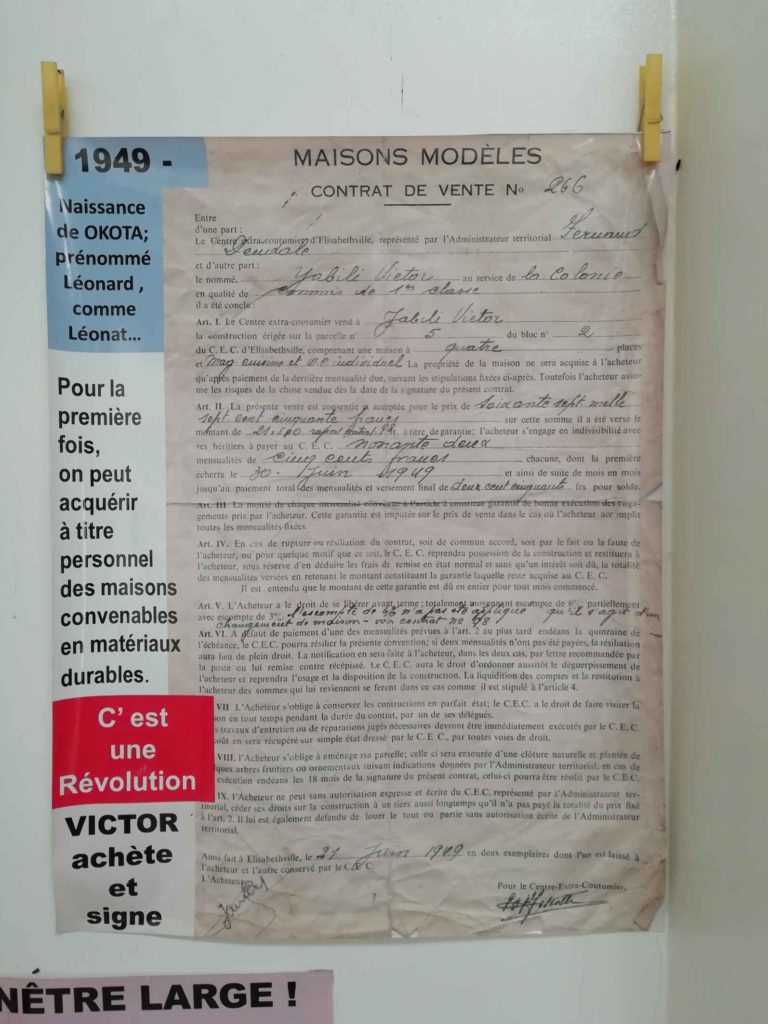

The neighborhood of Kamalondo in Lubumbashi, better known for its bars and nightlife, harbors a surprising destination: the small Yabili family museum. At once a museum of family, city, regional, and national history, its creation in 2014 was the sole work of its proprietor ‘maître’ Marcel Yabili, a magistrate and well-known fixture of the city’s civic and cultural life. The museum does not have regular hours. Most visitors are invited by its owner, who is not concerned with attracting a large audience, and it is unclear whether many locals come. The museum is housed in one of neighbourhood’s original houses constructed between 1919 and 1929. Kamalondo was the first of the city’s planned ‘native’ towns—exercises in segregation typical of the colonial era. Abutting the ‘neutral’ zone, it was separate from the white part of the city. Part of the neighbourhood was reserved for small single-family homes, one of which was purchased by Yabili’s father in 1949 (the original sale deed is on display.) The small houses with little front yards were meant to imprint the Catholic, nuclear family upon the colonized Congolese moving to Elisabethville in search of work.

This ideological orientation, embedded in the neighborhood, is also clearly reflected in the museum’s narrative about modernization and social mobility. The story of Marcel Yabili’s family—their migration from rural areas to Elisabethville and their lives in the city—serves as the museum’s central story. This journey is depicted as a gradual social climb, through the avenues of work, education, and civic life. A timeline anchors the presentation, combining the stories of colony, city, community, and family in both visuals and narrative. The family history at the heart of the exhibition, starting with the owner’s grandparents, sits within the chronological frame of colonial history. Family and local events are weaved into the fabric of world wars, royal visits, and epochal change. Family milestones, such as the birth of Marcel Yabili’s mother in 1925, are given the same attention as e.g. the construction of Pont (bridge) Gecamines and the Grand Hotel in the same year. Yabili links his own birth to the celebration of the end of World War Two. In 1947, one grandfather dies, a grandmother joins her children in Elizabethville, and the Prince Regent Charles visits the city in the aftermath of the war.

There is then a clear attempt to insert the local into the global and to project a cosmopolitan image of the city and its inhabitants. To that purpose, Yabili also layers the histories of other families into the displays. In most cases these are neighbourhood families, but there is also the story of the Italian Riccardo family, who spent time in the city because of the father’s position as a railway engineer. The Belgian royal family, their visits to Congo, and how these visits intersected with the lives of each generation of the Yabili family are also recurring elements in the narrative. For example, the visit of (then) Prince Albert to Congo in 1909 connects to family lore through the story of one grandfather who brushed the coat of the prince’s horse, while the other made one of the chairs on which the prince sat.

The museum display consists of a visualization of this timeline combined with an overwhelming amount of text. The texts are illustrated with historical documents that range from official documents (certificates, contracts) to family letters, pictures and photographs of the growing city. There are few objects (one of the old windows of the house, a gramophone, etc.), but the collection is growing through donations from community members (a colonial suit, vintage beer bottles, etc.) that are placed alongside the exhibition. The house is both subject and artefact of the museum. Its acquisition by the owner’s father Victor Yabili, the exhibition explains, reflected a changing conception of ownership from collective to individual that was initially mocked by Victor’s family. The house’s presence as a character in the family story also allows for interesting reflections on the commodity culture that comes with occupying such a house—the things one acquires and how all of these things (from irons to lamps to bicycles) become status indicators.

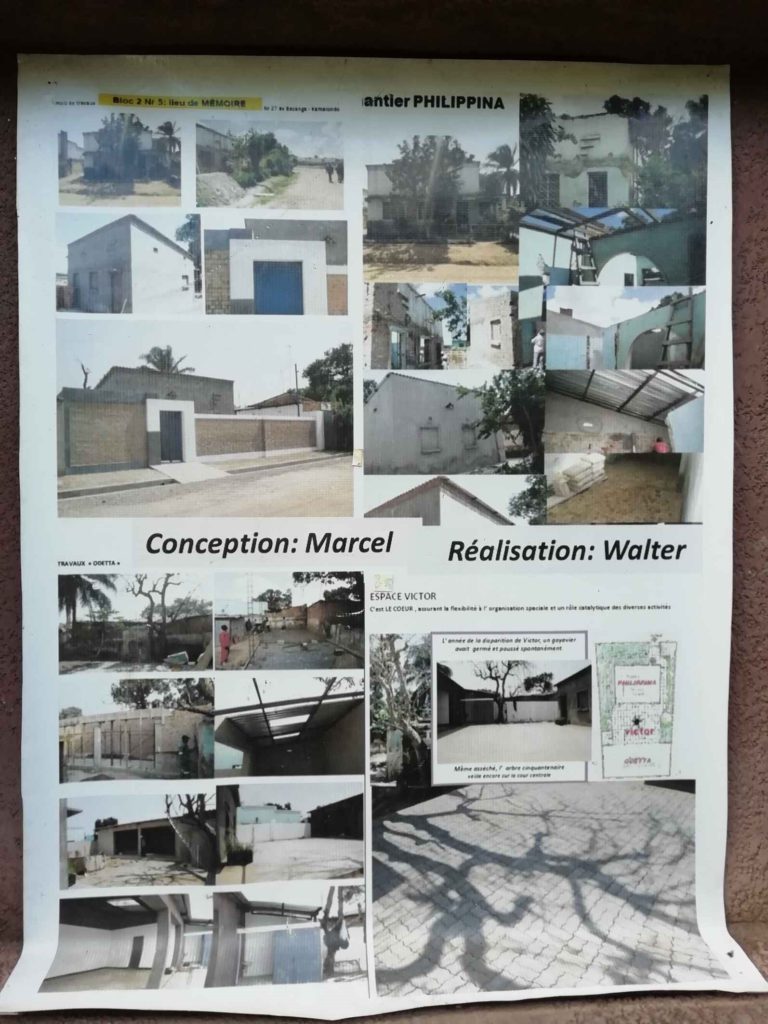

This entangled narrative synchronizes the family’s early urban story with the Congo’s colonization by Belgium, but peters out with the era of independence. The last date on the timeline is 1957. The last event mentioned is the Katanga secession and the subsequent UN occupation, referenced though children’s drawings and a diary entry from a teenaged Marcel Yabili, who would lose his father in 1963. From there, events skip ahead to Yabili’s recovery of the family house and its restoration. Yabili laments the (postcolonial) decline of the neighborhood, humourously pointing out his hopes that the evangelical church occupying Kamolondo’s former water purification station is praying for the health of inhabitants who have to live with the now-destroyed sanitary system.

On the one hand, the historical narrative presented is a conservative one of imperial expansion and modernization, heavily influenced by an old-fashioned type of colonial history. But on the other hand, there is a form of appropriation taking place—a doubling up of the narrative of discovery and exploration re-cast as a family history of movement and discovery from the countryside to the city into a different and better life and future. As such, it presents a proud history of modest roots and upward mobility, of the formation of a Congolese middle class. Can this admittedly narrow view of the past be read as a critique on the postcolonial present? It would seem so.

Although the Yabili family story is central, the story line that threads through the museum is not singular. Other family testimonies are added to the collection, as are their material donations. Although the central narrative is not (yet?) undermined by the additions, the crowd-sourcing of stories and objects makes for an interestingly organic museum. The re-invention of the house as a museum adds a unique element to a heritage landscape in which the state is otherwise dominant. This private initiative to insert a smaller story into a larger narrative has created a lieu de memoire that is at once deeply conformative to an older narrative about modernity yet simultaneously carries within it the ability for reflection upon the present.It is a fascinating look into the efforts of one man to take ownership of the history of a place via the history of his own family.