Nicole Eggers is assistant professor of history at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville and is currently completing a book manuscript tentatively titled ‘Unruly Ideas: A History of Kitawala in the Congo.’

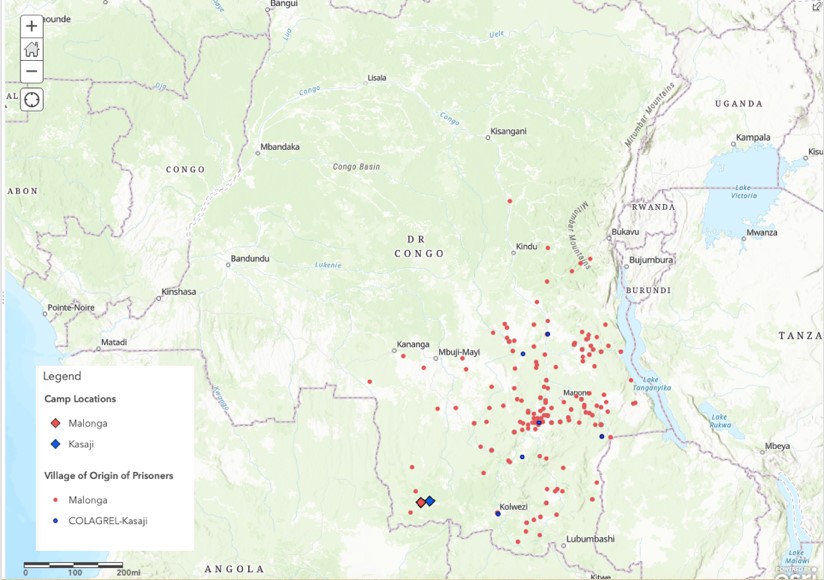

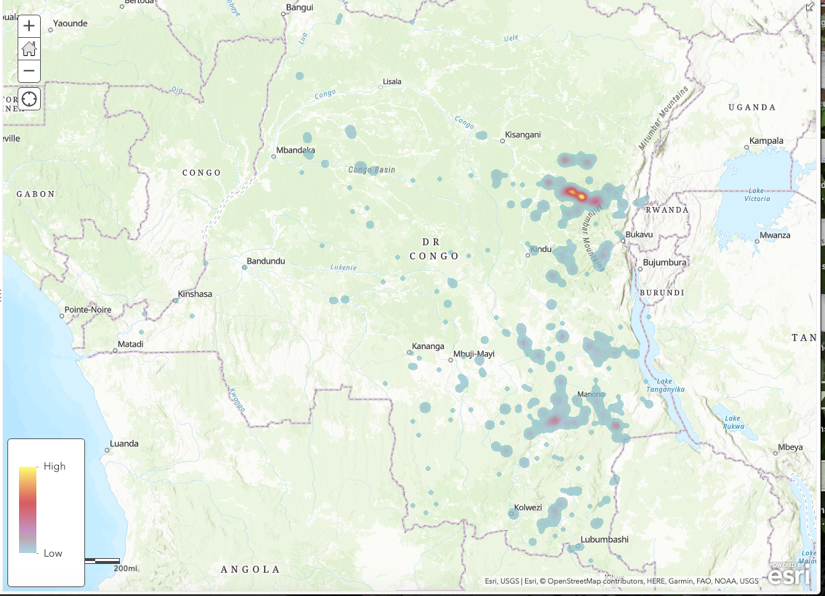

In the summer of 2018, I traveled to COLAGREL, a site located 18km from the small town of Kasaji, in what is today Lualaba province of the DR Congo. COLAGREL was built during the colonial era as an internment camp (or CARD – Colonie Agricole pour les Relégués Dangereuses) to house convicted leaders of the religious/healing/political movement Kitawala and their families. Kitawala was historically connected to the African Watchtower movement [Fields, 1985; Gordon, 2012; Higginson, 1992; Eggers, 2013 and 2015). And though its influence stretched far beyond the Copperbelt at its peak in the mid-20th century and it was greatly transformed as it moved through Congo, its history was still very much a Copperbelt history. COLAGREL, built in the early 1940s and in operation until independence, became the forced residence of hundreds of Congolese men, women, and children from various parts of eastern Congo [see Maps 1 and 2]. Many of these Kitawalists had been ‘relegated’ – the term the Belgians used for their policy of removal, detention, and surveillance of religious and political “dissidents” – since the mid-1930s, when they were originally sent to a different camp in nearby Malonga. In 1942, the colonial government abandoned the Malonga site for COLAGREL, mainly because they feared that Malonga’s proximity to the wider local population risked the spread of the movement from the camp and “contamination” of the region.

When I arrived to Lubumbashi in 2018, I wanted to visit COLAGREL to see both what remained of the internment camp and what kind of oral history existed around it. Though I had maps and descriptions from the archives, I lacked visceral understanding of the space. Moreover, during previous research with members of the Kitawalist community in Kalemie in 2014, I had been clearly told that if I really wanted to understand the history of COLAGREL, I had to go there. Inspired by the work of historians like Donatien Dibwe (2005) and Tamara Giles-Vernick (2001) who have emphasized the importance of memory and place, or “sites of recollection”, in understanding the past, I agreed with their assessment. The trip did not disappoint.

While I was, like all field researchers, aided by numerous people in this pursuit, much of the success of this trip can be attributed to the kindness, patience, and hospitality of one man: Pastor Theophile Molongo, the local leader of the Kitawalist church in Kasaji. I had met Pastor Molongo previously, when I chanced upon a large regional meeting of the church at one of its missions near Kalemie in 2010 while researching Kitawalist beliefs, practices, and history. When I – again by chance – turned up in the midst of a major regional meeting of the Kitawalist church in Lubumbashi in July 2018, this time asking about COLAGREL, Pastor Molongo interpreted it as a divine sign, and volunteered to travel with me to Kasaji. Pastor Molongo had actually been born in COLAGREL in 1952, after the colonial government had ‘relegated’ his father (and mother) there in 1947. So, he agreed to take me to the camp and tell me about its history and his memories of growing up there.

While there is not space here to convey all of the ways that my understanding of the history of COLAGREL – both during and after the colonial era – was enriched by this trip, let me offer just one example. When I was doing archival research about COLAGREL in Brussels, one of the more striking documents I found was a hand-drawn planning document for COLAGREL that depicted it as a cité jardin, a kind of idyllic ‘garden city’ – a popular concept in urban planning in Brussels in the early 20th century. Part of the turn toward developmentalism as colonial policy more broadly in the post-war years, and specifically as a tactic for trying to stop the spread of Kitawala, this conceptualization revealed something about the hopes of colonial officials that camps like COLAGREL could serve as spaces that would convince recalcitrant Kitawalists of the benefits of living peacefully within the colonial state. The legacies of this cité jardin plan can be seen today in the tree-lined central road of COLAGREL, and the lush mango forests that abut the camp.

But if the archive reveals the developmentalist hopes of these colonial officials, oral history reveals the price of their implementation. As we were walking through the camp one day, making our way to the grave of Mama Saint Nkulu Kwamwanya Adolphine (the first Kitawalist woman to die in the camp, whose grave is now a site of a yearly pilgrimage for many local Kitawalists ) we passed through the mango forest mentioned above. Pastor Molongo told me that in order to grow this forest, the Belgians transported in a load of mangoes. They then offered five mangoes to each of the prisoners who had been brought over from Malonga to build the camp. They were told to eat the mangoes and then plant their seeds. For each seed that did not produce a seedling, they were punished with one lash of the chicotte (whip).

COLAGREL is today a space that is haunted by the memories of such moments of profound cruelty and colonial violence. You can see it embodied in the prison building at the center of camp, where prisoners caught discussing Kitawala were confined as punishment. The walls of the tiny cells were painted black – to maximize the feeling of darkness and confinement. And yet, the descendants of many of those ‘relegated’ to the camp continue to live there and in nearby Kasaji. For them, the site embodies more than their oppression. It embodies the history of their endurance. But it is also a space where people live in precarity: though they were, according to their oral history, bequeathed this land by the prison director at Independence, they have no legal documents recognizing their claim. Telling their stories matters, not just for what it reveals about the history of the intimate experiences of ‘relegation’ for Kitawalist men and women, but because recognition of that history and its legacies matters for those who live there today.

Dibwe, Donatien, “History and Memory”. In John Edward Philips, Writing African History, Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2005.

Eggers, Nicole “Kitawala in the Congo.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin, 2013.

Eggers, “Mukombozi and the Monganga.” Africa: The Journal of the International African Institute 85, no. 3 (2015), 417-436.

Fields, Karen. Revival and Rebellion in Central Africa. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985

Giles-Vernick, Tamara, “Lives, Histories, and Sites of Recollection”. In White, Miescher, and Cohen, African Words, African Voices. Indiana University Press, 2001.

Gordon, David, Invisible agents: Spirits in a Central African history. Athens: Ohio University Press (2012).

Higginson, John, “Liberating the Captives: Independent Watchtower as an Avatar of Colonial Revolt in Southern Africa and Katanga, 1908-1941.” Journal of Social History, 26, no. 1, Autumn 1992, 55-80

Images by the Author (Aug 2018).