Hikabwa Chipande is a Lecturer & Researcher in Sports at the University of Zambia School of Education.

Missionaries, industrialists and colonialists introduced team sports such as football to the Central African Copperbelt of the Belgian Congo and Northern Rhodesia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries because they believed they provided an important form of leisure and cultural power that could be useful for educating, modernising and controlling colonised African labour (Chipande, 2016).

The booming Congolese copper mines in Katanga also drew in Belgian mineworkers, for whom football was an important leisure activity. In 1911 a ‘whites only’ Ligue de Football du Katanga was established in Élisabethville (now Lubumbashi) (Alegi, 2010). Football was integrated into the Belgian imperial project in the 1920s by the ‘unholy colonial trinity’ of the colonial government, Catholic Church and the Union Minière du Haute Katanga (UMHK) mine company that sought to ‘create a disciplined, efficient, moral and healthy African working class’ (Alegi, 1999). UMHK’s motto was “good health, good spirits, and high productivity” and it deployed an elaborate welfare system to control African leisure time and labour. Sport was also associated with colonial violence: for example, 100 striking African miners who converged on a Lubumbashi compound football ground in December 1941 demanding better conditions of service were massacred by colonial troops armed with machine guns (Goldblatt, 2008).

For Catholic missionaries, the game was a central part of their broader agenda of planned recreation and ‘Muscular Christianity’ that was intended to produce disciplined, healthy and moral subjects. The game was also meant to distract Africans from their colonial and capitalist exploitation (Akindes and Alegi, 2014). In 1925, Father Gregory Coussement formed the Élisabethville Football Association and by 1950, over 30 clubs were affiliated to it . By the end of the 1950s, the association had about 1,250-registered African football players and thousands of fans, making soccer one of the most popular pastimes for African mineworkers and their families in Katanga (Alegi, 1999).

A few years later, football was also introduced across the border in the Northern Rhodesian Copperbelt. The colonisation of Northern Rhodesia and the start of large-scale mining in the 1920s brought colonial officials and industrialists who played the game to the emerging mining towns. As in Katanga, Africans who went to seek mining jobs became interested and began to play the game in their communities. African teams in mining towns initially reflected the ethnic character and loyalties of African urban mineworkers: team names included ‘Bisa’ (made up of migrants from Bisaland), ‘Nyasa’ (from Nyasaland), ‘Nyika’ from Tanganyika etc. Matches between these teams provided an athletic spectacle that sometimes brought communities to a standstill as hordes of fans gathered around rudimentary grounds to watch and support their favourite teams (Chipande, 2016).

The popularity of soccer in the Copperbelt’s African mining compounds attracted the attention of colonial and mining authorities. They formed a Native Football Committee in 1936, entirely composed of white compound managers, to oversee and manage black football. Following the Copperbelt strikes of 1935 and 1940, the authorities realised that colonial and economic domination required an ideological and cultural component to complement rule by force. As had occurred in Katanga, they developed and strengthened welfare schemes for educating and controlling increasingly restless African labour. The authorities attended African football matches and funded some of the competitions, not only to exercise political control over African leisure and labour, but also because they feared that football gatherings would provide avenues for political agitation. This was also seen across the Congo River in colonial Brazzaville in the 1930s, when colonial authorities were forced to give African football in Bacongo and Poto-Poto townships serious attention because of the game’s popularity (Martin, 1995).

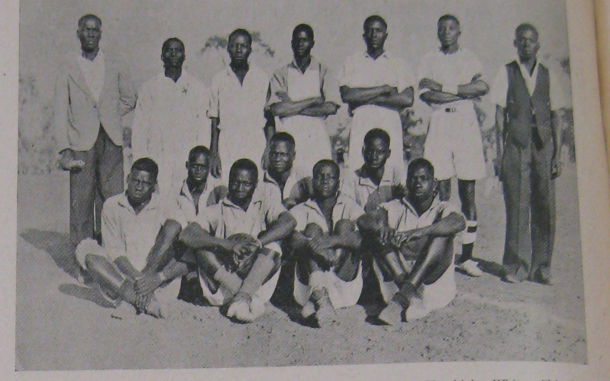

Authorities in both Katanga and Northern Rhodesia shared not only copper mining techniques, but also the use of football to control African labour to maximise copper production and prevent political agitation. This cross-border cooperation was exemplified in regular African soccer exchanges between the two mining regions. From the 1940s to the early 1960s, the Copperbelt African Football Association and the Élisabethville Football Association organised tours where the teams from Katanga played their Northern Rhodesian hosts, and vice versa. Katanga was the hub of soccer in Belgian Congo as it was the most industrialised region with thriving towns such as Élisabethville, Jadotville, and Kambove. Similarly, the Copperbelt was the heart of the game in Northern Rhodesia from the 1940s in the mining towns such as Luanshya, Kitwe, Chingola, and Mufulira: by this time, teams representing these towns were drawn from their multi-ethnic African communities.

These tours were not limited to the Central African Copperbelt but extended to the whole southern and eastern African region. In 1950, one of the very first known ‘unofficial sub-Saharan soccer championships’ was organised in Élisabethville. The competitors included a Bantu Football Association (JBFA) team from Johannesburg South Africa, a Copperbelt team under the Copperbelt African Football Association, a team from the Belgian Congolese capital Léopoldville (today Kinshasa), and a host team from Katanga. The Katanga team beat Léopoldville 2 -1 in the final that was played in Leopold II Stadium and watched by over 40,000 spectators (Alegi, 1999). The late 1950s and early 1960s saw the continuation of inter-colony football tours involving African soccer clubs from Katanga, Tanganyika, Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia and South Africa. This created what would become, with decolonisation, international football links that reflected the popularity of the game in the region.

Africans in the Central African Copperbelt appropriated the game from Europeans who had introduced and sought to use it as a tool for ‘civilising’ and controlling their labour. They turned football into a key form of black urban popular culture with thousands of spectators gathering every weekend in different mining towns to watch and support their preferred teams. Football exchanges within the region that had been initiated by colonial and mining authorities went on to strengthen networks and camaraderie among colonised Africans who shared a rich ancestral and economic history.

Today, Zambia and Democratic Republic of Congo enjoy a close relationship in economic, political and social spheres. Copperbelt border towns such as Chililabombwe (on the Zambian side) and Kasumbalesa (in the DRC) retain significant populations from ‘the other side’ that straddle the two territories. Congolese footballers play in Copperbelt football clubs and some Zambian players play in Katangese football clubs, showing that the relationship that exists between the two countries represent an enduring legacy of the socio-economic ties that can be traced back to the colonial and even pre-colonial era.

References

Alegi, P. 1999. “Katanga vs Johannesburg: a history of the first sub-Saharan African football championship, 1949-50.” African Historical Review. 31, 55-74.

Alegi, P. 2010. African Soccerscapes: How a Continent Changed the World’s Game. Athens: Ohio University Press.

Akindes, G. and Alegi, P. 2014. “From Leopoldville to Liège: A Conversation with Paul Bonga Bonga.” In Onwumechili, Chuka and Gerard Akindes, Identity and Nation in African Football: fans, community and clubs. London: Palgrave Macmillan Press.

Chipande, H. D. 2016. Mining for Goals: Football and Social Change on the Zambian Copperbelt, 1940s—1960s. Radical History Review. 125, 55-73.

Chipande, H. D. 2018. Challenge for the Ball: Elites, Fans and the Control of Football in Zambia’s One-Party State, 1973–1991. Journal of Southern African Studies. 44, 991-1003.

Goldblatt, D. 2008. The ball is round: a global history of football. New York: Riverhead Books.

Martin, P. 1995. Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.