Post by Miles Larmer, PI, ‘Comparing the Copperbelt’ project

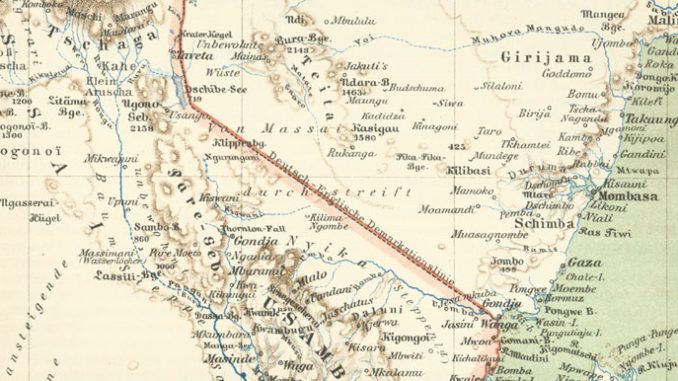

One of the great myths of African history is that the 1884-85 Berlin conference divided the continent into colonial territories with fixed borders that became the basis for independent nation-states. Historians such as Katzenellenbogen (in Nugent and Asawaju, 1996) have clearly demonstrated that ‘Berlin’ simply initiated a process of territorialisation that took decades to make real on the ground, and which was continually negotiated and contested by African societies themselves. However, it is also now clear that such contested territorialisation neither began with colonialism, nor ended with decolonisation: we are increasingly aware that pre-existing and new indigenous notions of appropriate spatial division interacted with official processes of mapping, border-drawing and state-making to draw and re-draw African boundaries and territories and what they meant to Africans themselves.

Historicising these processes was at the heart of a stimulating conference held at the University of Leipzig on 8 May 2017, entitled ‘Territoriality, Boundaries and Spatial Practices in Berlin’s Africa’. This event was organised by Leipzig’s Collaborative Research Centre 1199, which explores the conditions in which space is made, and spatial orders are established, in a context of historical and contemporary globalisation.

The conference brought together historians concerned with a range of time periods and places of African history, whose presentations helpfully problematized any assumption that border-making was essentially a top-down and specifically colonial initiative. Bas De Roo’s work, for example, demonstrates how new spatial relations between central African societies in what are today the Central African Republic, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) developed as a result of increasing engagement with local and global trade networks. Geert Castryck, focusing on Kigoma-Ujiji’s pivotal position over time, from the inland penetration of the Indian Ocean caravan trade, to the colonial border between Tanganyika, Rwanda-Urundi and the Belgian Congo, through to their successive nation-states (Tanzania, Burundi and the DR Congo): in all these periods, this urban settlement acted both as a border through which flowed goods and people, but which also functioned as a hub for the development of ideas about identities and how they should be articulated socially and acted upon politically.

Such findings are highly relevant for the Comparing the Copperbelt project. The border between Zambia and the DRC functions both as the basis for defining national and local identities, but also a channel for the flow of material and human resources and ideas. It provides as the basis for cross-border comparison, both by the project’s investigators but also by the historical actors – colonial and post-colonial states, mine companies, social scientists and Copperbelt communities – we are investigating.

In my own paper for the Leipzig conference, I investigate how Zambia’s first generation of post-independence diplomatic representatives used their postings in the DRC to articulate their understanding of how Zambia’s new national identity contrasted to that of its neighbour. This understanding was however complicated by the residents of both copperbelts, who had a decidedly different view of the appropriate spatial organisation of their society, and continued to define and act across the border and against state-based definitions of what it meant to be ‘Congolese’, ‘Zambian’, etc. Before and after independence, Copperbelt residents, notwithstanding the efforts of colonial and post-colonial states to render them fixed subjects of citizens, maintained familial and social relations and pursued economic activities on both sides of the border, sometimes by evading its controls and at others taking advantage of the differences it created.

One particularly stimulating presentation to the conference was provided by Achim von Oppen who, in explaining the lengthy process of border drawing between Angola and Zambia in the early twentieth century, demonstrated how the fixing of boundaries of riverine polities such as the Barotse kingdom had a long-lasting legacy for the relationship between those polities and the states into which they were uneasily integrated. Likewise, Aidan Russell’s paper on decolonising Burundi emphasises the invocation of the Kanyaru river dividing Rwanda and Burundi as a way of eliding these countries’ shared colonial histories and seeking to impose a settled past on a far from settled future. Such insightful works suggests the need for more comparative analysis of, for example, the border-drawing processes of different African states and the relationship between these exercises and the differential sense of belonging or exclusion among peoples of ‘border societies’ to one or more states. That is however a project for another day…