Post by Benoît Henriet, Research Associate in the History of Haut Katanga, DRC

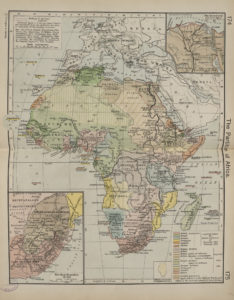

As many Africanists have already argued (Mbembe, 2000; Ferguson, 2006; Benton, 2009), empires did not cover space evenly, as suggested on the maps produced in the wake of the 1884-5 Berlin conference. On the contrary, colonial power was effectively concentrated around “enclaves” of economic and strategic interest and the “corridors” joining them to western controlled global markets. In vast swaths of territory, Western states’ sovereignty remained mostly formal. Mines, plantations, the shores of navigable waterways, roads and railway lines were however places that were a priority for subjugation by imperial forces. They attracted larger numbers of public servants, European private agents and African intermediaries, and it was in those territorial clusters of ‘Afrique utile’, as they were sometimes called by French imperial authorities, where colonial desires for social engineering were most strongly expressed. These settings provided opportunities to implement new models of labour and social organisation, where profit making was seen as inseparable from improving the living conditions of indigenous workers. However, such plans, drafted in Europe, often turned into frustrated endeavours in the field.

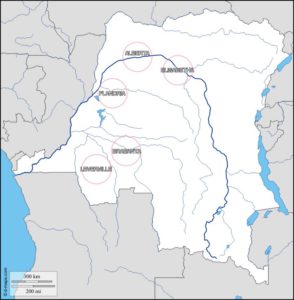

In Belgian Congo, the company town of Leverville, a pilot project of the Huileries du Congo Belge (HCB), illustrates well the shortcomings of such “model” colonial capitalism. Leverville emerged in 1911 out of the converging interests of the Belgian State and the British company Lever Brothers (later Unilever), producer of the Sunlight brand of hygienic products. For Belgium, Lever Brothers was an ideal partner, a company hailed for the social policies it had put in place in mainland Britain. The model city of Port Sunlight, in the suburbs of Liverpool, host to its headquarters and main industrial facilities, offered rows of suburban houses for its workers. Its aim was to foster, through its planned leisure amenities and strict internal rules, middle-class values among its working-class population. Attracted by the potential riches of the Congo in oil palms, as well as by the challenge of transplanting the Port Sunlight ideal to the tropics, Lord Leverhulme, the Company’s chairman, signed an agreement with the Belgian government to create HCB, a subsidiary of the Lever consortium, which aimed to exploit five palm oil concessions scattered throughout the colony. For the aging industrialist Lord Leverhulme, HCB was expected to become the crowning achievement of his own brand of “moral capitalism”. As he wrote in a private letter in 1924, a few months before passing away, the Huileries were “a business like none other we have. Perhaps Port Sunlight comes nearest to it in social work” (Lewis, 2008, 177).

Of the five HCB concessions, the most profitable was Leverville, named after the chairman, in which were concentrated the densest palm groves of the colony. From the start, however, reality fell short of the vision of social order that Leverhulme wished to attach to his name. Not only was Leverville rarely profitable, it also failed to become the “beacon of progress” dreamt of in Europe. Leverhulme firmly believed that of wage labour, alongside the schools, hospitals and rations the company promised to provide, would attract workers. However, the men expected to willingly join the company fled in front of its recruiters. The harshness and danger of the labour demanded from them, living in camps away from their homes, as well as the poor remuneration HCB offered, failed to interest them.

Failing to find sufficient voluntary workers, HCB partnered with Belgian colonial agents to forcibly recruit Congolese men. Although forbidden by law, public servants and company employees toured Leverville’s neighbouring villages in joint tax collection and recruitment operations. Such collaborations may have been encouraged by the concession management’s bribing of colonial administrators. Furthermore, the company’s social policies did little to meet the objectives set out on paper. Rations offered to workers were considered insufficient and unappealing by both Congolese workers and Belgian doctors. The expensive and ambitious medical programme that Lever Brothers claimed to deploy in its Congo concession was also heavily criticised by the colony’s health inspectors.

Leverville, a project born out of the shared desire of the Belgian government and of Lever Brothers to build a “moral” form of capitalism in Central Africa, turned out to be a disappointment even in the eyes of its founders. It was a place of “indescribable ugliness”, according to Leverhulme’s personal secretary, marred by violence, hunger, illnesses and failing profitability. Before the Second World War, HCB survived only because its chairmen were determined to see it succeed against the odds. Indeed, Lever Brothers invested vast amounts of money in HCB, despite its failure to reap profits. The Huileries’ business model was, in fact, hardly likely to generate benefits. Infrastructure building in the Congo was costly and slow, transporting palm fruits and oil to Europe was crushingly expensive, and there was never a sufficiently large workforce to collect fruits and man the oil mills. HCB also failed to compete against a highly efficient emerging palm oil industry in Southeast Asia.

The interwar history of Leverville offers an interesting angle for the study of capitalism in colonial Central Africa and beyond. Far from only being attracted by the prospect of profit-making, companies could also foster imperial projects driven by the will to achieve a significant moral endeavour. Making Leverville a success was partly a matter of hubris for Leverhulme and his successors. Despite (indeed, perhaps because) of HCB’s losses and the numerous impediments encountered in its early existence, the Lever Brothers board kept supporting its Congolese venture through its faith in this paternalistic model.

Leverville bears a striking resemblance to another failed utopia of tropical capitalism: the Brazilian town of Fordlandia, brilliantly described by Greg Grandin (Grandin, 2009). In 1927, Henry Ford purchased a sizeable plot of land in the Amazon to build a vast rubber concession. Fordlandia was expected to become a vast rubber plantation coupled with rows of model housing, hospitals and amenities. Like Port Sunlight for Leverhulme, Ford hoped that the town would instil Western middle-class values among its Brazilian workforce. However, the garden-city’s inhabitants refused to comply with Ford’s puritan ideals; bars and brothels flourished on the edges of town, while petty criminality plagued the community. Moreover, the rubber plantations were poorly designed and offered disappointing yields. However in spite of its many failings, Ford kept pouring large amounts of money into the town that carried his name.

Both Leverville and Fordlandia can be seen as extreme examples of “model” capitalism. These dreams stemmed from the minds of ambitious and successful captains of industry, who managed to achieve their paternalist visions in the Western world before striving to reproduce them in a radically different socio-cultural context. In spite of their highly particular nature, these stories of frustrated hubris invite us to consider the affective dynamics beyond (post-)colonial capitalism, to see how emotions, morals and ideology constitute driving forces behind the capitalistic practices of resource extraction in the global South.

Bibliography:

Lauren Benton, A Search for Sovereignty. Law and Geography in European Empires , 1400-1900, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

James Ferguson, Global Shadows. Africa in the Neoliberal World Order, Durham-London, Duke University Press, 2006.

Greg Grandin, Fordlandia. The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City, New York, Metropolitan Books, 2009.

Brian Lewis, “So Clean”. Lord Leverhulme, Soap and Civilization, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2008.

Achille Mbembe, De la Postcolonie. Essai sur l’imagination politique en Afrique contemporaine, Paris, Karthala, 2000.