Reuben Loffman’s forthcoming book, Church and State in the Belgian Congo, 1909-1962, based in part on his PhD fieldwork, will be published in the Cambridge Imperial and Postcolonial Studies Series by Palgrave in late 2019/early 2020. He is a regular contributor to The Conversation and has appeared on Al-Jazeera, RFI English, Actualite.cd and PowerFM. He teaches in the School of History, Queen Mary University of London.

Archives have fascinated historians ever since the discipline became professionalised in the late nineteenth century. Yet the notion that Africa did not have archives that could be triangulated in the Rankean model meant that for some historians, such as Hugh Trevor-Roper (1965), the continent did not have a purposive history. But Trevor-Roper’s dictum was immediately disproven. Jan Vansina, one of the founders of modern African history, pioneered the idea of using oral traditions as sources (1965). The spoken word became very important for Africanists, therefore, as they pursued their projects across the world’s second largest continent. But it is nonetheless important to remember something the late Professor Terence Ranger once advised me at one of St. Anthony’s fabulous post-grade researcher days and that was that it is a mistake to think that written archives only exist in Europe and spoken ones only in Africa. Africa, if one looks hard enough, can be a rich source of archives.

But what is an archive in the first place? In a very real sense, written archives at least are troves of documents pertaining to the institution(s) that we wish to examine. Historians have come a long way, though, since Leopold von Ranke’s time when archives were believed to have been a scientifically accurate means of adjudging the past. In fact, as Natalie Zemon Davis (1987) has reminded us, there can be a good deal of fiction in archival repositories as authors seek to justify themselves often in untruthful ways. Ann Laura Stoler (2010: 139) explains that, in colonial contexts, archives were not passive objects but in fact could arm a colonial administration with ‘evidence, and, in so doing, justify inaction, reduce allocations, and abort policy.’

However they were used and whatever fiction may be in them, historians naturally always hope that archives will be bountiful and relevant. Oftentimes we are disappointed – which only serves to make documentary discoveries even more exciting! I experienced both emotions when I was in the Congo researching for my doctorate, undertaken from 2007 to 2011, on the making of colonial rule in northern Katanga (now Tanganyika province).

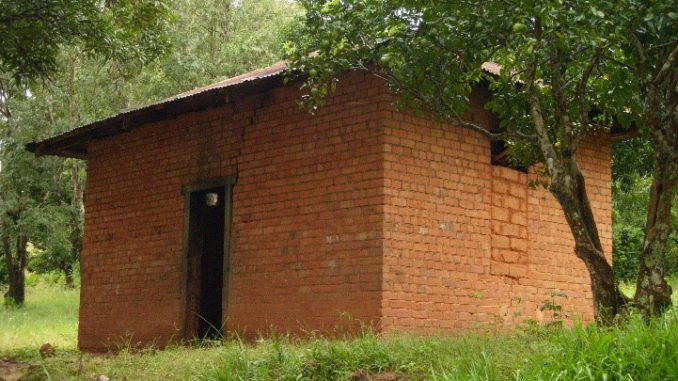

I had initially wanted to work on a longue durée history of violence in colonial Katanga but was disappointed to find hardly any of the archives pertaining to the period after colonial rule remaining. One of my biggest disappointments during my fieldwork in the DR-Congo occurred in an old Seventh Day Adventist mission in a village called Bigobo in Kongolo territory, Tanganyika, in April 2009. My friend and I had driven by motorcycle through the rain along a mud path to get to the mission and at first I was thrilled to be told by the locals that there was a library there (see picture above). However, upon closer inspection, it was clear that the building had been burned out. I asked why this had occurred and was told that it had been used as a base by the invading Rwandan-backed Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD) army during the Second Congo War in the early 2000s. The story behind the RCD invasion is one that at some point I will turn to in my research. But my only reaction in 2009 was immense frustration that I had made such an effort to find an archive only for it to be destroyed.

So there were plenty of frustrations during my doctoral fieldwork but there were also several breakthroughs. I greatly enjoyed working with the team at the Centre d’Études et de Recherches Documentaires sur l’Afrique (CERDAC) at the University of Lubumbashi. CERDAC had a number of documents that helped sharpen my thinking about the construction of colonial chieftainship in Kongolo territory.

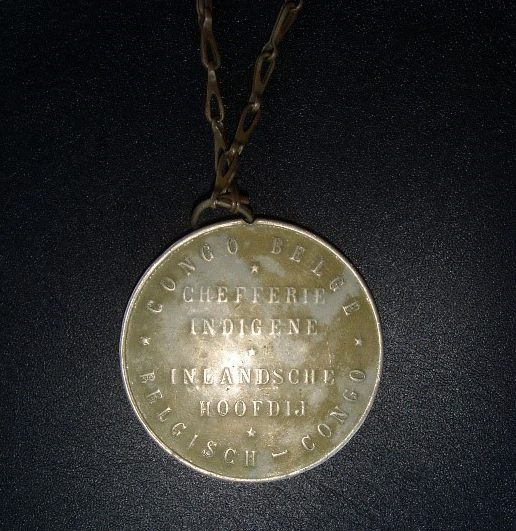

While institutions such as CERDAC do exist in the DR-Congo, they are not many institutionalised archives in the country. One of the most important cultural shifts I had to adapt to in the DR-Congo was that many people have created their own non-institutional archives. I was fortunate to meet a number of individuals who were prepared to show me papers relating to the activities of the Church and/or the colonial state. Chiefs in particular held a number of colonial-era papers justifying their position that they were happy to show me for obvious reasons. These papers largely – though not exclusively – consisted of family trees showing the ancestors of the particular chief whose they happened to be. What was striking about most if not all of these papers, as well as the chiefs’ oral histories, was that they all began in around the 1880s. The late nineteenth century coincided with the invasion of the eastern savannah by a range of Zanzibari slaver-merchants who often established proxies called sultani in localities who could deliver slaves to them (Vansina, 1990: 242). Although correlation does not equal causation with regard to Zanzibaris and local chiefs, it did suggest that the relationship between these two sets of actors required further consideration. Aside from documentary evidence, it was interesting to see a colonial chief’s medal (see picture, left).

A number of historians, such as Hein Vanhee (2005: 79-82), have drawn our attention to the importance colonial officials placed on medals and correspondingly how significant they were for enthroned individuals in demonstrating their alliance with the Belgian regime. Such medals gave chiefs a very tangible sign of colonial authority, although its very existence demonstrates that there were contests over chieftainship in rural Congo, hence the need for chiefs to demonstrate their credentials. It is also unclear how seriously a chief’s subjects took the colonial medals as credentials of his authority, especially given that chiefs’ demands for labour and tribute were so onerous. It was indeed not symbolic demonstrations of power, but rather the threat of force, not least the chicotte whip and colonial prisons, that curtailed anti-colonial rural rebellion in the Belgian Congo.

Overall my fieldwork taught me to be kind and patient with yourself if you are doing fieldwork in the DR-Congo. It is not easy getting information and there are all sorts of difficulties but there are equally many interesting finds to be made so don’t give up!

Bahati njema!